Authored by Stefan Gingerich, MS, Senior Research Analyst, StayWell

As senior research analyst for StayWell, Stefan Gingerich is responsible for researching program effectiveness, developing surveys and normative statistics, and applying scientific research to benefit StayWell clients. Stefan is a member of the Heath Enhancement Research Organization’s Research Studies committee and the International Society for Infectious Diseases, as well as a proud graduate of the University of Iowa.

As senior research analyst for StayWell, Stefan Gingerich is responsible for researching program effectiveness, developing surveys and normative statistics, and applying scientific research to benefit StayWell clients. Stefan is a member of the Heath Enhancement Research Organization’s Research Studies committee and the International Society for Infectious Diseases, as well as a proud graduate of the University of Iowa.

Wellness champion networks (WCN) are among the tactics used by employers to help build grassroots support for employee health and well-being (HWB) initiatives. The influence of social networks on health is fairly well-studied, though most of the work to date focuses on family members or close friends.1 Some studies have suggested that the support of one’s peers, including WCNs, is associated with improved workplace health outcomes.2,3 However, little empirical research has been done on how to best support these networks.

The HERO Health and Well-being Best Practices Scorecard in Collaboration with Mercer© (HERO Scorecard) includes questions related to the use and support of WCNs, so an analysis was conducted to determ

ine how employers are using and supporting WCNs as part of their HWB initiatives, and if this differs by the number of employees at an organization.

Prevalence of Wellness Champion Networks and Related Support Strategies

Of 396 employers who have completed version 4 of the HERO Scorecard to date, 55% reported using a wellness champion network to support employee HWB. This varied by employer size, as discussed below. For employers that reported using WCNs, the most commonly-reported strategy for supporting them was “regularly scheduled meetings for the champion team” (77%). Other strategies were less common, with 56% reporting use of a WCN toolkit, 54% reporting use of rewards or recognition for wellness champions, and 47% reporting that they provide training for wellness champions. It should be noted that the HERO Scorecard does not provide a definition of each of these strategies, so there is room for some interpretation among the respondents, in terms of what each strategy entails.

These basic findings offer some food for thought. Companies looking to start or enhance a WCN could use these results to inform priorities. It appears companies have accepted the time-honored idea that in order for a group of people to function as a true network, meetings are imperative. In an increasingly connected society, ample interaction between members of the WCN can occur via email, online portal, or impromptu one-to-one calls, but regularly scheduled meetings were still an important strategy for more than 3 out of 4 WCNs. And without the “regularly scheduled” qualifier in the HERO Scorecard question, this number may have been even higher. For instance, last year, in an unpublished study of StayWell clients, a similar question without the “regularly scheduled” qualifier showed that over 90% of organizations with a WCN held meetings at some frequency, either by phone or in person.

In contrast, a majority of respondents offered no training, or they offered such minimal training that they didn’t feel it merited mention when they were completing the HERO Scorecard. It seems reasonable to assume that wellness champions will be more successful with thoughtful guidance as to what is expected of them, what resources are available to them, and where they can go with questions. Conversely, having no training may limit the effectiveness of the network. Future research in this area would be beneficial, specifically to understand the influence of different kinds of training on the success of WCNs.

Use of Wellness Champion Networks by Employer Size

For the purposes of this analysis and commentary, organizations were divided into three groups, consistent with HERO Scorecard benchmarking reports. “Small” organizations were those that reported having less than 500 employees. “Large” organizations were those that reported having 5,000 or more employees. “Mid-size” organizations were those in between those two categories.

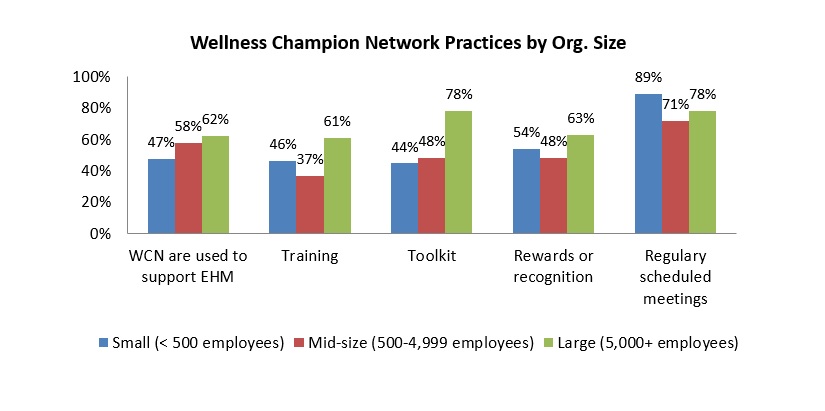

According to HERO Scorecard data, large employers were more likely to have WCNs in place. In fact, there was a fairly clear relationship between the number of employees an organization had and the likelihood that they had a WCN. Small organizations had the lowest prevalence of using WCNs (47%), and large organizations (5,000+ employees) had the highest prevalence (62%). Mid-size organizations were in the middle, with 58% having WCNs.

According to HERO Scorecard data, large employers were more likely to have WCNs in place. In fact, there was a fairly clear relationship between the number of employees an organization had and the likelihood that they had a WCN. Small organizations had the lowest prevalence of using WCNs (47%), and large organizations (5,000+ employees) had the highest prevalence (62%). Mid-size organizations were in the middle, with 58% having WCNs.

Likewise, large organizations were more likely than small and mid-size organizations to offer training (61%), toolkits (78%), and rewards/recognition (63%) in support of WCNs. Here, though, a clear pattern based on organization size was not present. Small organizations were more likely than mid-size organizations to offer training (46% and 37%, respectively) and rewards (54% and 48%, respectively), but slightly less likely to offer toolkits (44% and 48%, respectively). Small organizations were most likely to have regularly-scheduled meetings (89%).

As the field of workplace health and well-being matures, opportunities for small and large organizations to learn from each other will grow. Large organizations may do well in this instance to reflect on why small organizations are more likely to have regularly scheduled WCN meetings.

Similarly, small organizations may want to consider why large organizations are more likely to support their wellness champions with training, toolkits, and recognition. This comprehensive approach may be more impactful, though it also may require more resources.

Finally, it’s important to keep in mind that all networks are truly unique, and these support practices may not make sense for some organizations (e.g. a network of three people may not need such formality). Practitioners should, therefore, take what seems most useful from these data and apply it to their work, leaving behind findings that they feel will not benefit them. Each organization may need to use distinctly different organizing principles to get support strategies in place. That, among other things, is what makes future research on these networks a very interesting prospect.

- Smith KP, Christakis NA. Social networks and health. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2008;34:405-429.

- Webel AR, Okonsky J, Trompeta J, Holzemer WL. A systematic review of the effectiveness of peer-based interventions on health-related behaviors in adults. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):247-253.

- Terry PE, Grossmeier J, Mangen DJ, Gingerich SB. Analyzing Best Practices in Employee Health Management: How Age, Sex, and Program Components Relate to Employee Engagement and Health Outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(4):378-392.

Data cited in this commentary are based on HERO Scorecard responses submitted through December 31, 2015.