It seems fitting that I returned from our Think Tank in Kansas City feeling that “best practices” in the health promotion profession need a lot more explaining. After all, Missouri is the “Show Me State,” a place where skepticism and needing convincing are a badge of cultural pride. One source suggests that the “show me state” nickname came from the frequent instruction needed when novices took up mining. Relative to professions like law or medicine, ours is a young field, and though we are applying findings from a growing science base, it is also a fast changing one. We titled this think tank, “Forging a Fresh Course for Worksite Health and Well-being,” and our primary aims were to update HERO members on the current state of our field and to review strategic planning methods and tools that can help move organizations, and our profession, toward a desired future state. Watch for a future blog post from HERO’s Dr. Jessica Grossmeier where more key learnings and links to materials and a think tank webinar will be included. Though I’m proud of how much value we’ve mined so far in our young profession, this think tank has me considering that we’re still far from hitting the real pay dirt.

HERO’s President Karen Moseley opened the Think Tank by describing key tenets of “Blue Ocean Strategy.” She alluded to the similarities between military structures and how corporations are organized via hierarchies and accountability. Moseley’s many examples of strategically successful innovators showed us how finding breakthrough ideas is a group process steeped in openness, curiosity and risk taking. Indeed, General Eisenhower said: “In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.” In this spirit, we organized sessions throughout the day that moved us from hearing from experts about what is presently occurring in the field to exercises designed to consider where change is needed. In particular, we discussed the elements of program design captured by best practices scorecards, and we generated ideas about what elements were missing or should be better defined.

Using “Hoshin planning” methods, we based our visioning exercise of the day on the recently published “Workplace Health in America Survey.” We were honored to have these results presented to us by the lead author and investigator Dr. Laura Linnan, a professor from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Based on a key finding from the study, we generated dozens of ideas in response to this vision statement: “Comprehensive programming occurred in 7% of companies in America in 2004 and moved up to 17% in 2017. It is 2030 and 50% of companies in America now invest in comprehensive approaches to improving employee health and well-being. What happened? How did we get there?” By “comprehensive approaches,” we were referring to how the survey used the Healthy People 2010 definition of a comprehensive as:

(1) health education, (2) supportive social and physical environment, (3) integration of the program into the organization’s structure, (4) linkage to related programs such as employee assistance programs, and (5) worksite screening and education.

How well are we using best practices?

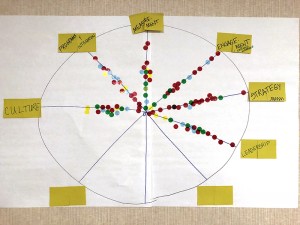

In a recent open access journal editorial, I argue that: “confusion remains about what constitutes a comprehensive program.” I discuss how recent studies that conclude worksite wellness doesn’t work are errantly positing that participation in one best practice element, health education, is what constitutes a comprehensive program. Ideation by HERO members at this think tank affirmed that achieving a vision of more companies adopting comprehensive approaches will require a lot of convincing in the years ahead that health education programs like classes or coaching are but one element, albeit a vital one, of health and well-being initiatives designed for population wide impact. When I asked participants to vote on how effective our field is in each of the commonly cited best practices elements such as engagement, organizational support or education programs, I was struck by the flat distribution of participant views with an equal number of high, medium and low ratings.

In a recent open access journal editorial, I argue that: “confusion remains about what constitutes a comprehensive program.” I discuss how recent studies that conclude worksite wellness doesn’t work are errantly positing that participation in one best practice element, health education, is what constitutes a comprehensive program. Ideation by HERO members at this think tank affirmed that achieving a vision of more companies adopting comprehensive approaches will require a lot of convincing in the years ahead that health education programs like classes or coaching are but one element, albeit a vital one, of health and well-being initiatives designed for population wide impact. When I asked participants to vote on how effective our field is in each of the commonly cited best practices elements such as engagement, organizational support or education programs, I was struck by the flat distribution of participant views with an equal number of high, medium and low ratings.

I will continue reflecting on several “Blue Ocean” possibilities generated by our think tank miners. Many ideas generated about our profession’s future state related to developing better capabilities for building organizational cultures of health. Though current scorecards have many items relating to culture, such as CDC’s above “supportive social and physical environment” and HERO’s “leadership and organizational support,” I came away from this session thinking that “culture” is a distinct best practice element that needs better defining and differentiating. Similarly, participants were in agreement that leaders are a vital enough element to also be assessed and studied independently. These two putative best practice elements were the exceptions to the even distribution of ratings for the other elements with most participants voting our profession as low or medium in effectiveness in building better cultures and leaders. This is supported by the findings of a literature review on cultures of health written by HERO’s Culture of Health Study Committee where we found that healthier cultures are correlated with healthier employees, yet we found scant evidence of organizations that had intentionally or successfully transformed their culture to produce health improvement.

While the role of culture and leaders were ascendant in our planning exercises, “program integration” and “connecting with communities” were elements considered to be lesser predictors of success. Moseley reminded participants that advancing community health has been a core strategic priority for HERO and that she would consider what role we can play in better establishing the vital role community connectivity could play in workplace well-being best practices. Interesting discussions also ensued concerning the differences between “engagement” and “the employee experience” with some suggesting these should also be considered as distinct best practices elements. I’ve previously suggested that “little ‘e’ engagement” is when we define engagement as how often employees participate in wellness programs. In contrast, “big ‘E’ engagement” is when employees are in the vaunted “flow” as they work; they’re excited by and committed to the overall mission and cultures of their organizations. Perhaps adding the term “employee experience” to our best practices nomenclature will help us better parse between these different processes and outcomes relating to engagement. Per Moseley’s promise, I’d argue that best practices in connecting employers to their communities is a sure way to drive big “E” engagement and support an ideal employee experience.

Mining into New Veins and Deeper Depths

An impromptu exercise I tried during this think thank was to ask participants to array themselves across the room as to whether they agreed or disagreed with this statement: “Recent studies that are based on one program element and conclude that wellness doesn’t work are doing our profession a service.” Those who strongly agreed were asked to go to one end of this large room, those who strongly disagreed went to the other end, and those in between spread out as to their leanings. I was fascinated by the visual effect of our profession’s brain trust spread into a relatively flat bell curve. That is, there were somewhat more in the middle on this question but the distribution was mostly evenly spread. Those on the “strongly agree” end of the room said they went there because the evidence suggests that most well-being initiatives in America are indeed mostly about one element: education program offerings. If we assess the health benefits accruing to the few that participate in education programs and apply those results to the health status of the whole population, it’s useful to show that, of course, this won’t produce a population level return on investment. Those on the “strongly disagree” side of the room worried that the average reader of such studies won’t have the wherewithal to understand that what gets represented as a comprehensive approach is simply not such.

I would have joined those in the middle. I’ve felt that when poorly designed interventions are studied by otherwise stellar researchers, it’s a disturbing missed opportunity. On the other hand, as longtime HERO member Jack Bastable told me, “research is also supposed to tell us what doesn’t work.” Spoken like a true Missourian. To be sure, better explaining “best practices” and informing future research with a convincing case about what constitutes a comprehensive approach is the kind of deep arduous mining we all need to keep sweating over. When we hit pay dirt, let’s bring our findings to the show me state.

References

“Missouri Nicknames,” www.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Missouri

Dwight D. Eisenhower Quote, https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/dwight_d_eisenhower_164720

Laura A. Linnan, ScD, Laurie Cluff, PhD, Jason E. Lang, MPH, MS, Results of the Workplace Health in America Survey, Research Article, First Published April 22, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117119842047 Vol 33, Issue 5, 2019

Paul E. Terry, PhD, “Workplace Health Promotion Is Growing Up but Confusion Remains About What Constitutes a Comprehensive Approach,” https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117119854618

Jennifer Posa Flynn, MS1, Gregg Gascon, PhD2, Stephen Doyle, MS, MBA3, Dyann M. Matson Koffman,DrPH, MPH, CHES4, Colleen Saringer, PhD, MEd5, Jessica Grossmeier, PhD, MPH6, Valeria Tivnan, MPH, MEd7, Paul Terry, PhD6, “Supporting a Culture of Health in the Workplace: A Review of Evidence-Based Elements,” American Journal of Health Promotion, vol. 32, 8: pp. 1755-1788. First Published May 28, 2018.