By Xiaohui (Sherry) Tang, PhD, Research Coordinator, Baylor College of Medicine

By Xiaohui (Sherry) Tang, PhD, Research Coordinator, Baylor College of Medicine

As an experienced researcher and behavioral epidemiologist, Dr. Xiaohui (Sherry) Tang is skilled in epidemiology, health promotion, and data analysis. She is strongly interested in design, implementation, and evaluation of worksite well-being initiatives and promotion of healthy workplace culture. Sherry holds a Ph.D. in Public Health focused on Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth).

Health and well-being initiatives have been introduced to employers over the past few decades with goals ranging from improving employees’ health, performance and productivity, to reducing medical costs, disability and absenteeism. There is no simple answer to the question, “Do employee health and well-being initiatives work?” because it depends on the specific goals of each organizational sponsor, the quality of the initiatives implemented, and the contextual environment supporting them. Effective initiatives are characterized by strong engagement strategies, ongoing program monitoring and management, and years of long-term maintenance.1, 2 The HERO Health and Well-being Best Practices Scorecard in Collaboration with Mercer© (HERO Scorecard) includes questions on the use of best practices such as strategic planning, participation strategies, and program evaluation to inform the development of effective program implementation. The HERO Scorecard also assesses employer use of individually targeted lifestyle management services and the impact of the overall health and well-being initiative on health risks and medical plan cost.

Prevalence of individually targeted lifestyle management services and forms of delivery

Of 628 organizations who have completed the HERO Scorecard, 77% offer individually targeted lifestyle management services that allow for interactive communication between an individual and a health professional or expert system. The most commonly used approach to deliver an intervention was phone-based coaching (77%), followed by web-based interventions (65%), onsite group classes (54%), email or mobile (SMS) (51%), onsite one-on-one coaching (43%), and paper-based bidirectional communication between the organization and the individual (17%).

Impact on Health Risk and Medical Cost

Overall, 42% of the 484 organizations providing these data reported improvement in health risk and 30% reported a positive impact on medical cost trend. Only 10% that measured health risk reported no improvement, and only 12% that measured medical cost trend reported no improvement. Notably, however, 36% had not attempted to measure change in health risk and another 12% were not confident that the results valid even though they had attempted to measure them. Similarly, 45% had not attempted to measure change in medical cost, and another 12% had measured but were not confident that the results are valid.

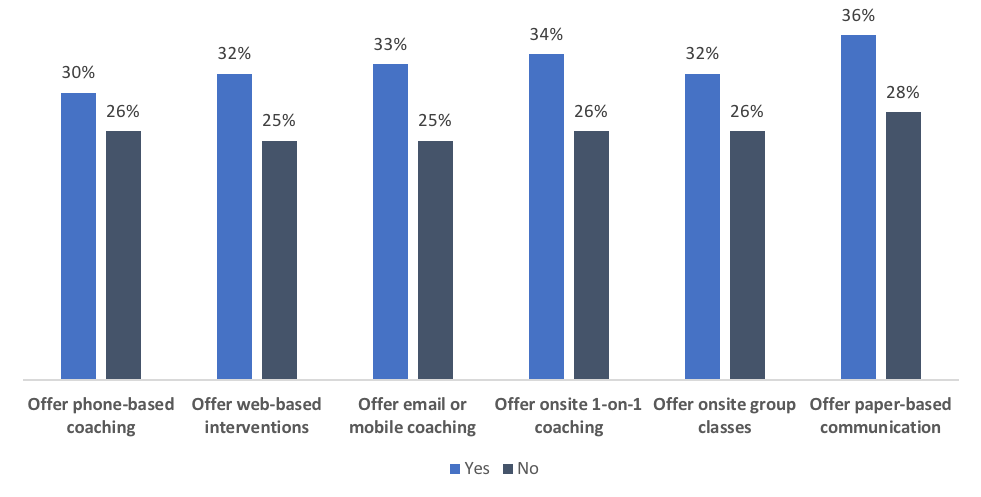

Among 836 organizations responding to the health improvement question, a much higher prevalence of reported health improvement (29% vs. 9%) was found among organizations that offered targeted lifestyle management services (29%) than those that did not offer services (9%). Among the much smaller sample of 628 organizations responding to the question about providing specific lifestyle management services, meaningful prevalence differences of reported health improvement were also found between organizations providing and not providing those services, respectively: phone-based coaching (30% vs. 26%), web-based interventions (32% vs. 25%), email or mobile (SMS) (33% vs. 25%), onsite one-on-one coaching (34% vs. 26%), onsite group classes (32% vs. 26%), paper-based bidirectional communication (36% vs. 28%).

Impact on Health Improvement Based on Provision of Coaching

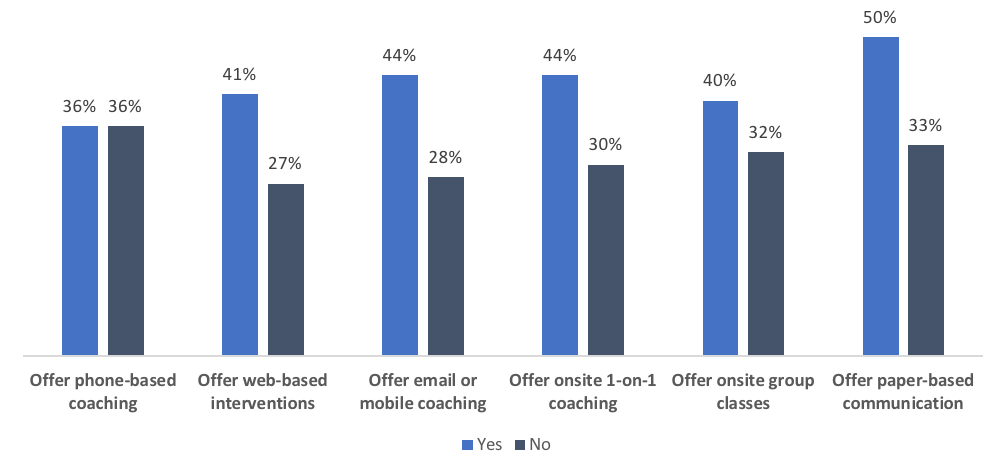

A similar pattern was found for medical cost trend: a much higher prevalence of improvement in medical trend (36% vs. 10%) was found among organizations offering and not offering lifestyle management services. With one exception, differences were found in the prevalence of improved medical cost trend between organizations that provided lifestyle management services and those that did not: web-based interventions (41% vs. 27%), email or mobile (SMS) (44% vs. 28%), onsite one-on-one coaching (44% vs. 30%), onsite group classes (40% vs. 32%), paper-based bidirectional communication (50% vs. 33%). Somewhat surprisingly, the prevalence of reported improvement in medical cost trend was the same (36%) among organizations that did or did not offer phone-based coaching. However, it is important to recognize that these are descriptive statistics unadjusted for organizational differences, participation rates, and other factors that may have affected the observed results.

Impact on Medical Cost Based on Provision of Coaching

Conclusion

This analysis yielded three informative, actionable findings.

- Individually targeted lifestyle management services are prevalent in organizations and there are a variety of forms of delivery. Offering a combination of learning and behavior change experiences is common among organizations seeking to improve population level health and medical cost outcomes.

- Over half of the organizations did not report having valid data related to employee health risk or medical cost trend. For organizations intent on understanding the effectiveness of their various interventions, these results demonstrate the value of measuring and reporting on outcomes.

- Offering individually targeted lifestyle management services was associated with much higher rates of improvement in health risk and medical cost trends.

While these findings provide additional support for the value of implementing and evaluating lifestyle management services within a best practice health and well-being strategy, they must be interpreted with caution. Because the results were correlational, causal relations cannot be determined. This study was also based on company-level self-reported data rather than medical claims analysis. Similarly, health improvement findings were based on employee self-reports, not on an analysis of objectively-measured health or biometric data.

Despite such limitations, the results are very helpful for benchmarking and shed further light on the relationship between the use of lifestyle management services and subsequent health and medical trend improvements. The fairly small incremental improvements tell us that a very significant amount of work remains to be done in order to improve individual outcomes and result in medical cost savings for employers. Well-controlled internal or vendor evaluation is necessary for those organizations intent on determining the impact of their specific health and well-being initiatives on employee health risks and medical costs.

This commentary is based on data from the HERO Scorecard Benchmark Database through December 31, 2017.

References

1. Serxner S, Gold D, Meraz A, Gray A. Do Employee Health Management Programs Work? Am J Health Promot. 2009;23:1-12.

2. Goetzel RZ, Henke RM, Tabrizi M, et al. Do Workplace Health Promotion (Wellness) Programs Work? Journal Occup Environ Med. 2014;56:927-934.

3. Musich S, White J, Hardley SK, et al. A more generalizable method to evaluate changes in healthcare costs with changes in health risks among employers of all sizes. Popul Health Manag. 2014;17:297-305.

4. Serxner S, Alberti A, Weinberger S. Medical cost savings for participants and nonparticipants in health risk assessments, lifestyle management, disease management, depression management and nurseline in a large financial services corporation. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26:245–252.