By Laura Hamill, PhD; Chief People Officer & Managing Director, Limeade Institute

By Laura Hamill, PhD; Chief People Officer & Managing Director, Limeade Institute

Organizational support for well-being is the extent to which an organization provides the resources, communication, reinforcement, and encouragement to enable employees to improve well-being. When individual improvement or behavior change happens, the “ecosystem” around that change has to be supportive—if it isn’t, change either won’t happen or will be less likely to be sustainable. In the workplace, the organizational “ecosystem” has to provide the policies and practices, visible leadership and manager support, role modeling, nudges and defaults to fully support well-being improvement.

The concept of perceived organizational support is not a new one1 — but it’s relatively new as applied to employee health and well-being. For example, research has shown that safety behaviors are improved when employees perceive that there is organizational support.2-4 More recently, Flynn5 found that participation in a variety of health screenings and health and well-being programs increased as the degree of organizational support increased.

The HERO Health and Well-Being Best Practices Scorecard in Collaboration with Mercer© (HERO Scorecard) offers valuable data to better understand the role of organizational support in well-being programs. To examine the relationships between types of organizational support and employee perceptions about it, an analysis was conducted of the HERO Scorecard database including responses from over 811 unique organizations.

Senior Leadership Support

One of the more well-accepted contributors to organizational support is leadership support, and the HERO Scorecard asks organizations about several specific leadership support practices. Descriptive analyses found that just over half (53%) of the organizations completing the HERO Scorecard report that their leaders are actively participating in health and well-being programs. However, there was a large gap between participating and the next most frequently reported type of leadership report. Specifically, the next three types of support reported were as follows:

- 28% of organizations have leaders who publicly recognize employees who participate

- 27% of organizations have leaders who articulate business relevance of well-being

- 23% of organizations have leaders who are role models for health and well-being

More than a quarter of responding organizations (26%) said “none of the above,” meaning leaders don’t support well-being in any of the ways assessed on the HERO Scorecard.

Managerial Support

Only 14% of organizations say managers are held accountable to improve well-being in their organizations. When asked whether mid-level managers and supervisors are supported in their efforts to improve the health and well-being of employees within their work groups or teams, only 13% of organizations said managers were given a lot of support. Another 37% said managers were given some support, and more than half (51%) of organizations said managers were given little or no support.

A recent study found that participants who reported high levels of well-being had more favorable perceptions of organizational support than those reporting low well-being.6 Researchers also found that managers were the most important contributor to overall perceptions of organizational support.6 Other important contributors included having tools and resources that support well-being and having senior leadership support.

Leadership Support and Outcomes

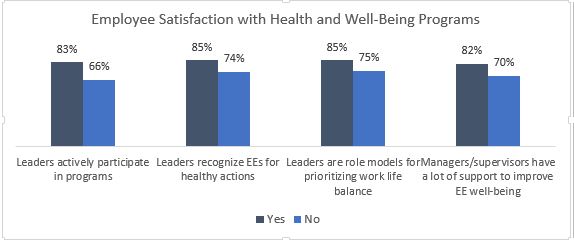

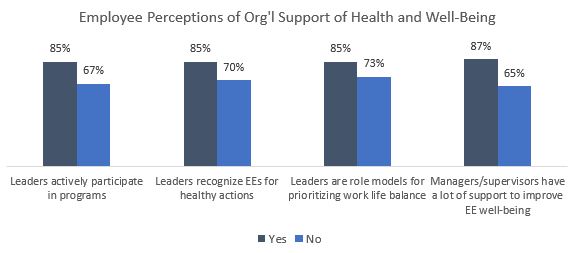

Subsequent HERO Scorecard analyses compared organizations with higher levels of leadership support to organizationally-reported employee satisfaction rates. One HERO Scorecard question asks employers to report the percent of employees who say they are satisfied with the employee health and well-being program. Another question asks employers to report the percent of employees who are in agreement that the employer supports their health and well-being.

- Organizations whose leaders actively participate in health and well-being programs reported much higher median employee satisfaction rates with health and well-being programs (83%) and also reported employee agreement that their organization supported their well-being (85%) compared to organizations whose leaders did not actively participate (66% and 67%, respectively).

- Organizations whose leaders publicly recognize employees for healthy actions and outcomes reported higher median employee satisfaction rates (85%) and employee agreement that their organization supported their well-being (85%), compared to organizations whose leaders did not recognize employee healthy actions (74% and 70%, respectively).

- Organizations whose leaders are role models for prioritizing health and work-life balance reported higher median satisfaction rates (85%) and employee agreement of organizational support (85%), compared to organizations whose leaders were not role models (75% and 73%, respectively).

- Manager support was measured based on responses to the question, “Are mid-level managers and supervisors supported in their efforts to improve the health and well-being of employees within their work groups or teams?” Organizations whose managers and supervisors were provided “a lot of support” had much higher levels of employee satisfaction with wellness programs (82%) compared to organizations reporting “some support” (76%), “not much support” (78%), and “no support” (70%). Likewise, organizations whose managers and supervisors were provided “a lot of support” reported higher median levels of employee perceptions of organizational support of their health and well-being (87%), compared to organizations reporting “some support” (80%), “not much support” (71%), and “no support” (65%).

Conclusion

These findings suggest that organizations that want to be perceived as caring about the well-being of their employees and having employees who are satisfied with their well-being initiatives need to enable, reinforce, and encourage leaders and managers to care about the well-being of their people. Well-being initiatives need to stop being thought of as “plug and play” programs that check the well-being box, and, instead, consider how the culture and practices of the organization support people as people.

This commentary is based on data from the HERO Scorecard Benchmark Database through September 30, 2017

- Rhoades, L. & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived Organizational Support: A Review of the Literature, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87, No. 4, 698–714.

- Credo, K.R., Armenakis, A.A., Feild, H.S., & Young, R.L. (2010). Organizational Ethics, Leader-Member Exchange, and Organizational Support: Relationships With Workplace Safety. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, Vol. 17: 325.

- Hofmann, D.A. & Morgeson, F.P. (1999). Safety-Related Behavior as a Social Exchange: The Role of Perceived Organizational Support and Leader-Member Exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(2): 286-296.

- Mearns, K.J. & Reader, T. (2008). Organizational support and safety outcomes: An un-investigated relationship? Safety Science, 46: 388-397.

- Flynn, J. (2014). Understanding the importance of organizational support. HERO Employee Health Management Best Practices Scorecard in Collaboration with Mercer, Annual Report 2014 (pp 12-13). Available at HERO-health.org/hero-scorecard.

- Limeade & Quantum Workplace (2016). Well-Being and Engagement Report. Available at: https://www.limeade.com/2016/09/well-being-engagement-report/

Laura Hamill, PhD, has over 20 years of experience helping companies be more strategic with their people. She is currently the Director of Research at The Limeade Institute and Chief People Officer at Limeade, where she leads the People Team, nurtures the culture of improvement and develops employee engagement strategies. She specializes in the intersection of employee well-being and culture. Prior to Limeade, Laura owned Paris Phoenix Group, an organizational research and assessment firm, focused on aligning employee engagement and culture. At Microsoft she spent a decade as the Director of People Research. She earned her Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from Old Dominion University and a B.S. in Psychology from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.