Megan Flanagan is a Wellness Consultant with PacificSource Health Plans in Portland, Oregon. She works with private and public-sector employers throughout the state to implement successful workplace wellness programs. As a Master’s of Public Health graduate from Utah State University, Megan served on the Utah Health Improvement Plan Committee and is a former Utah Worksite Wellness Council member. Megan also has a Bachelor’s degree in Nutrition and Psychology, and is a certified personal trainer and yoga instructor. She is passionate about inspiring wellness in individuals and teams by engaging employees, changing organizational culture, and improving health outcomes. Outside of work, Megan is an avid trail runner, non-fiction reader, and founder of an online community called Strong Runner Chicks.

Megan Flanagan is a Wellness Consultant with PacificSource Health Plans in Portland, Oregon. She works with private and public-sector employers throughout the state to implement successful workplace wellness programs. As a Master’s of Public Health graduate from Utah State University, Megan served on the Utah Health Improvement Plan Committee and is a former Utah Worksite Wellness Council member. Megan also has a Bachelor’s degree in Nutrition and Psychology, and is a certified personal trainer and yoga instructor. She is passionate about inspiring wellness in individuals and teams by engaging employees, changing organizational culture, and improving health outcomes. Outside of work, Megan is an avid trail runner, non-fiction reader, and founder of an online community called Strong Runner Chicks.

There is substantial discussion about the positive impact that social support has on health & well-being (HWB) programs and employee health behaviors, yet much of it is focused on links to individual rather than organizational well-being.1 Many researchers point to the social ecological model and social influence model to explain the way in which individuals change their behavior in response to influences of a social environment.2 Social networks also have a significant impact on the health of an individual, particularly in the environments in which people live, play, and work.3 For example, a study of a web-based health intervention found that social ties were significant predictors of higher participant engagement and behavior change.2 Despite social influence theories, however, there is not much research examining the impact of social strategies on the overall effectiveness of an organization’s HWB initiative.

The HERO Health and Well-being Best Practices Scorecard in Collaboration with Mercer© (HERO Scorecard) measures several components of HWB initiatives, including an organization’s perceptions about the effectiveness of their program and implementation strategies, use of social strategies, and types of social strategies used to promote participation in HWB programs.4 This commentary examines the relationship between organizational use of social strategies and perceived program effectiveness. Additionally, it looks into the relationship between the types of social strategies used and organizations’ perceptions of the effectiveness of their HWB programs.

Results

Of the 1,719 organizations that completed the Scorecard in the January 12, 2015 to September 30, 2019 time period, 1,398 organizations (81%) reported using one or more social strategies to encourage participation.

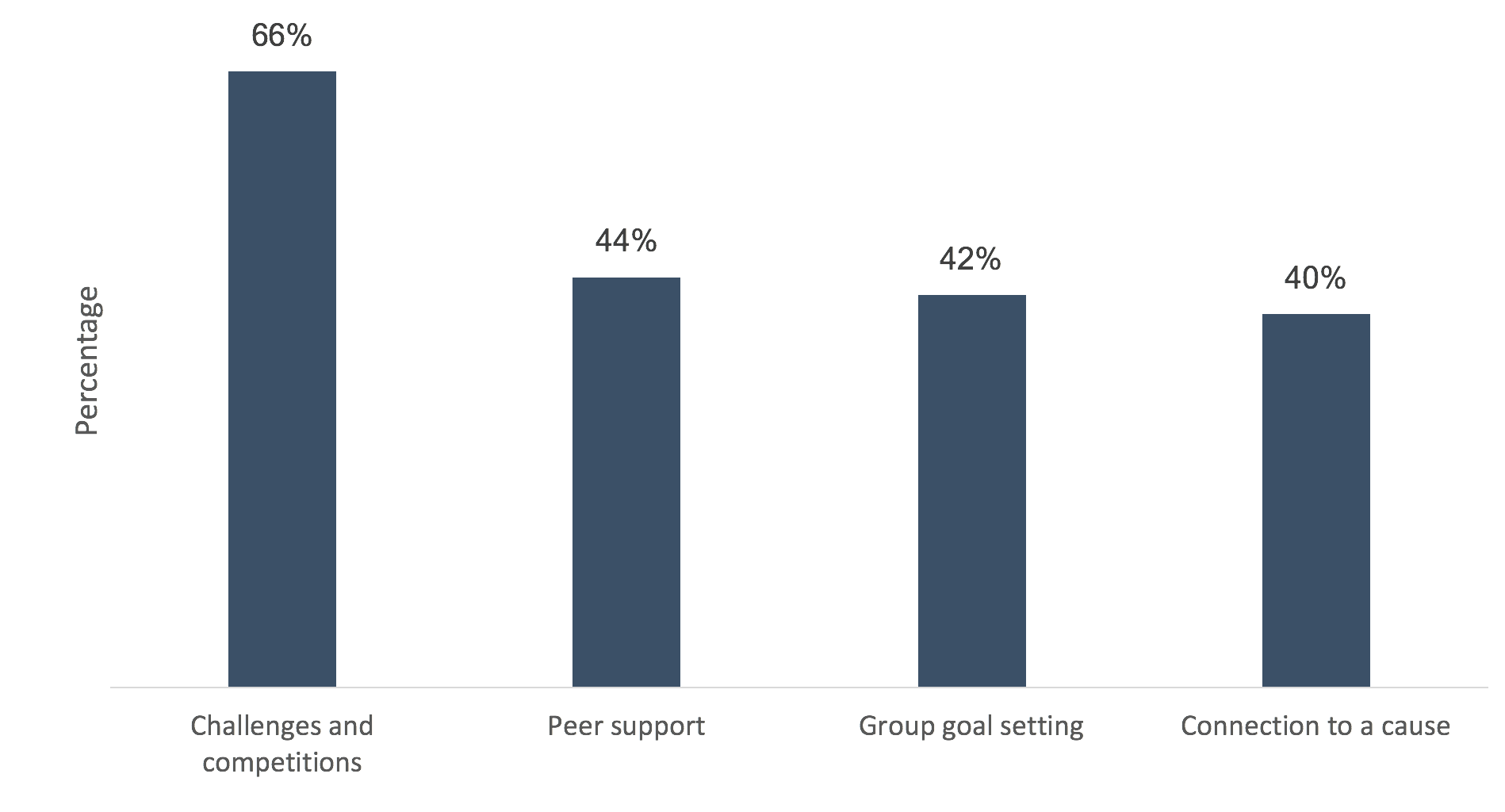

Social strategies measured in the HERO Scorecard include challenges and/or competitions, peer support, connection to a cause, and group goal setting. The percent of organizations that reported using each strategy is as follows:

- 66% use challenges and/or competitions (such as games);

- 44% use peer support (such as buddy systems or interventions including social components);

- 42% use group goal setting (a common health promotion activity with a common goal);

- 40% use connection to a cause (such as charity contributions

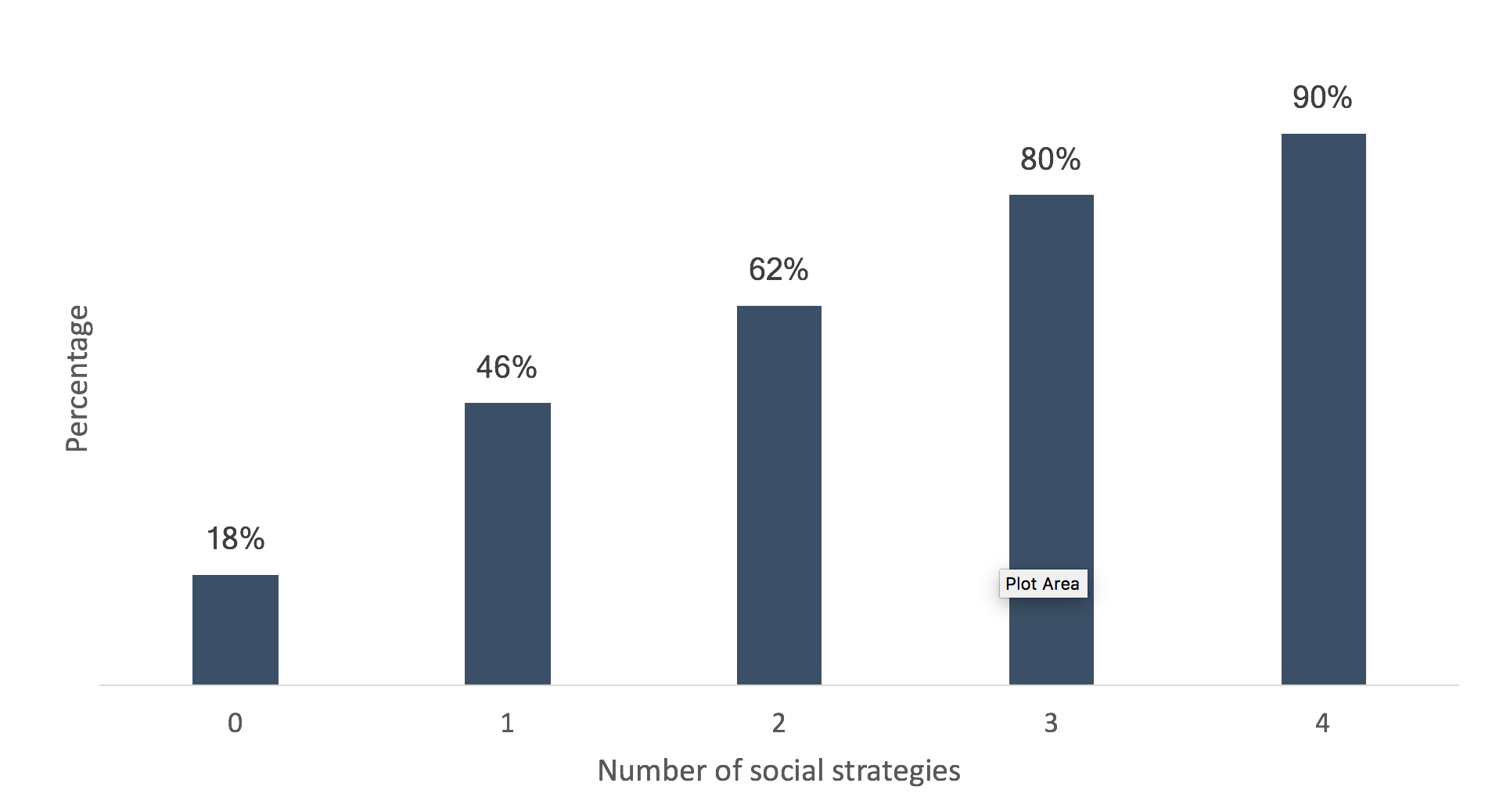

Effectiveness increased dramatically as the number of social strategies increased:

- 0 social strategies (n=418), 18% perceived program to be effective or very effective

- 1 social strategy (n=328), 46% perceived program to be effective or very effective

- 2 social strategies (n=301), 62% perceived program to be effective or very effective

- 3 social strategies (n=307), 80% perceived program to be effective or very effective

- 4 social strategies (n=365), 90% perceived program to be effective or very effective

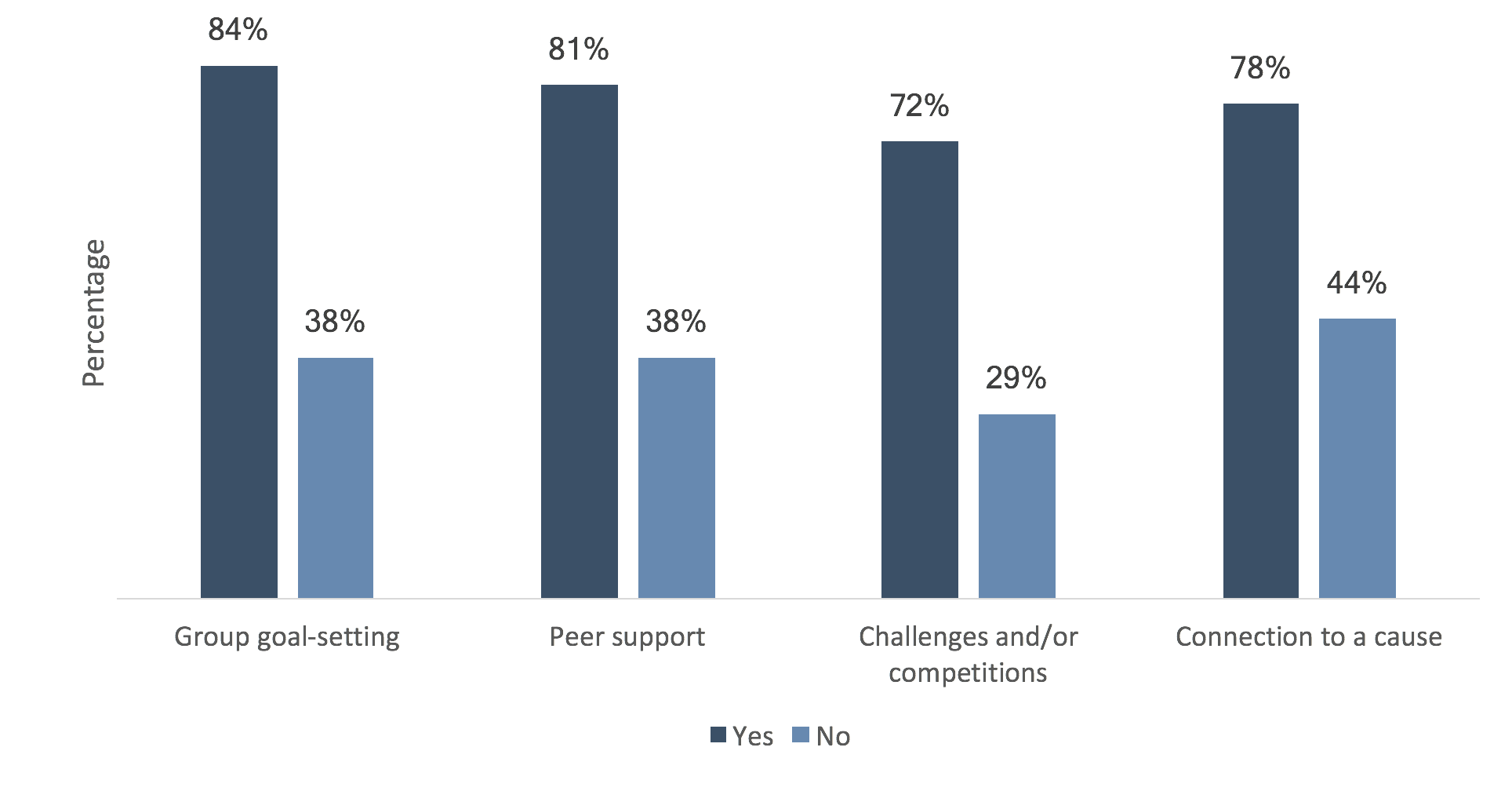

Which strategies are associated with higher effectiveness ratings?

For all four social strategies offered, there was a direct and substantial relationship between the use of the strategy and the likelihood that organizations reported their program to be effective. Group goal setting and peer support were most strongly associated with program effectiveness, but challenges and/or competitions and connections to a cause were also clearly linked with greater program effectiveness.

Group Goal-Setting – 84% of organizations with targeted group goal-setting activities reported their programs were effective, versus 38% without goal-setting activities.

Peer Support – 81% of organizations offering peer support reported their programs were effective, versus 38% without peer support.

Challenges and/or Competitions – 72% of organizations with challenges or competitions reported their programs were effective, versus 29% without challenges or competitions.

Connection to a Cause – 78% of organizations who connected their participation to a cause reported their programs were effective, versus 44% without connection to a cause.

When reviewing social strategies, it is important to recognize the important role that environmental social opportunities play in an individual’s autonomy to engage in health-related decision making, and prior research presents the case for organizations to incorporate social strategies into their HWB initiatives.2,3 The findings from this analysis showed that the more social strategies an organization integrated into their HWB initiative, the higher the likelihood they perceived it to be effective. The vast majority of organizations (90%) that offered 4 social strategies reported their HWB program to be effective, compared to only 18% reporting effectiveness who offered no social strategies.

This relationship that more social strategies were linked to more program effectiveness may be because the more strategies an employer uses, the more likely it is that employees will respond to at least one strategy. While some employees may be more likely to participate in company-wide competitions, others may prefer partner goal-setting activities. A 2015 study by Quantum found that physical activity preferences varied by age.5 For example, 20% of Millennials preferred company-wide exercise challenges, while only 5% of Boomers preferred these and, instead favored corporate-funded community events. Based on these findings, offering a variety of social strategies may motivate more employees with different preferences to participate in HWB program offerings, thus improving the effectiveness of the program. Given the emerging research on the potential health detriments related to loneliness and social isolation, connecting employees to one another may be more important now than ever. By incorporating multiple social components into a program, such as group goal setting, challenges and peer support, these results suggest organizations may be able to substantially increase the likelihood that their program will be effective, and, therefore, successful.

Implications for Practice

This analysis presents several implications for practice, one being the importance of social strategies for integrating into an organization’s HWB program. Incorporating more social strategies is associated with higher levels of program effectiveness and presents the case for social ties to well-being. There are many pathways linking social connection to longevity, including higher risk for a number of chronic diseases and all-cause mortality.1 Stanford researchers also found that 97% of participants who reported a high level of well-being or a particularly low level of well-being noted the presence or lack of social connections in their stories, respectively.6

The most important finding from this analysis is the strong link between the use of social strategies and its relationship to an organization’s perception of higher levels of HWB program effectiveness. This link is supported by other research including a study finding that team characteristics were a predictor of physical activity changes among team members in a worksite wellness competition.2 The importance of social ties to well-being presents a case for incorporating team components into an organization’s HWB program.

Despite their strong connection to higher levels of perceived HWB program effectiveness, the prevalence of social strategies being used is still gaining traction. Among organizations that completed the HERO Scorecard, 40-44% reported using peer support, group goal setting, or connection to a cause, and 66% reported using competitions. There is limited use of social strategies, despite their association with improved health and business outcomes, such as higher levels of participation, greater employee engagement, and increased levels of physical activity.7,8 HWB program strategists have an opportunity to improve their program’s effectiveness through increased use of social strategies. Further research examining the relationship between types of strategies and employees’ perceptions of effectiveness of a wellness program could help support HWB practices for organizations.

This commentary is based on data from the HERO Scorecard Benchmark Database through September 30, 2019.

HERO would like to thank and acknowledge the following HERO Scorecard commentary reviewers: David Anderson (VisioNEXT, LLC), Kerry Evers (Pro-Change Behavior Systems), Stefan Gingerich (StayWell/WebMD Health Services), Jessica Grossmeier (HERO), Mary Imboden (HERO), and Steven Noeldner (Mercer).

References

- Johnson SS. Social connection. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2018;32(5): 1304–1307.

- Poirier J, Cobb NK. Social influence as a driver of engagement in a web-based health intervention. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012 ;14(1):e36. DOI: 10.2196/jmir.1957.

- Golden SD, McLeroy KR, Green LW, Earp JA. L, Lieberman LD. Upending the Social Ecological Model to Guide Health Promotion Efforts Toward Policy and Environmental Change. Health Education & Behavior. 2015; 42(1_suppl):8S-14S.

- Health Enhancement Research Organization. HERO Scorecard Health and Well-being Best Practices Scorecard in Collaboration with Mercer. HERO Scorecard Benchmark Database through December 31, 2018.

- Hackbarth N, Brown A, Albrecht H. Workplace Well-Being. Quantum Workplace & Limeade. 2015:1-65.

- Avery E, Rich T, Ahuja N, Winter S. Stanford WELL for life: learning what it means to be well. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2017;31(5):444–456.

- Leahey TM, Crane MM, Pinto AM et al. Effect of teammates on changes in physical activity in a statewide campaign. Preventive Medicine. 2010;51:45–49.

- Zahrt O. Leadership support and the effectiveness of wellness initiatives. HERO Health and Well-being Best Practices Scorecard in Collaboration with Mercer 2018 Progress Report. 2018:30-33.